|

|

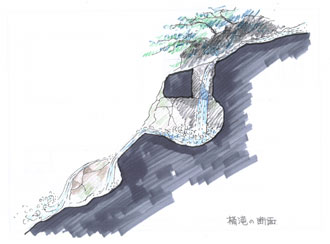

Oketaki Falls The rough waters of the Japan Sea break mercilessly onto the black rocks and reefs along the coast of the Noto Peninsular as if gnawing away at it, while the white surf billows like the foam from the mouth of a raging beast. Leaving such sights behind and proceeding west by car for about 20 minutes following the twists and turns of the coastline from Wajima, we soon come to the district of Ohzawa, which is well-known for its windbreak of bamboo. Another two kilometers further down the road is Kami-Ohzawa, or Upper Ohzawa. A little before Ohzawa halfway down a slope there is a notice on the left relating the Wankashi Legend, literally the “bowl-lending legend,” a piece of folklore prevalent all over Japan. Here, too, there is a small sign directing us to the Oketaki Falls. After following the Ohzawa Forestry Road a little way we come to a parking area and a notice oard on the left describing the falls. Alighting here we then need to walk down a twisting, densely forested path. Soon the sound of crashing water can be heard ahead. It’s the Oketaki Falls. It’s an astonishing sight. A torrent of water is falling through a gaping hole in the roof of a small cavern. It is just as if the bottom has fallen out of a large tub. The water then fills a basin and overflows down the rocks below. It is one of the few such falls in the whole of Japan and is designated as a Cultural Property of Special Interest in Ishikawa Prefecture. To the left of the falls there is a small shrine to Fudoson, a member of the Buddhist pantheon. During the last war, local women would offer prayers here for the safe return of their husbands and sons from the battlefields. A number of large trees surround the falls, with Japanese hackberry, chestnut and walnut amongst their numbers. There are wisteria vines, too, and before the Pacific War only a small patch of the sky was visible above the falls. Consequently, it is said that small children were frightened to go there because if was such a dark and ominous place. Furter up-stream from the Okitake Falls there are six more waterfalls including the Soryunotaki Falls but they are difficult to reach. Seven to eight hundred meters further on there is a cave known as the Komori-ana. It is said that fugitive warriors who fought for the Heike clan lived in the cavern after their defeat in the Genpei War, which raged in the twelfth century in fact, ancient stories and legends abound here. The Wankashi Legend is just one. Another tells tales of a woodcutter and charcoal maker called Chota and an old badger. |

|

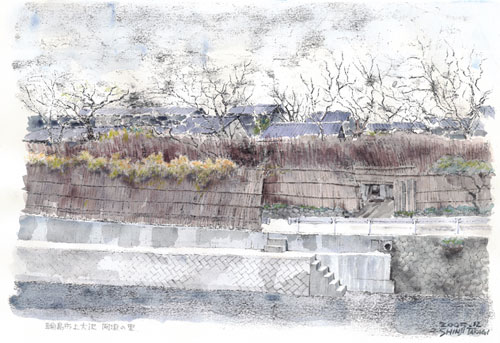

| In the latter part of the nineteenth century, Maeda Nariyasu, who was the 13th head of the Maeda clan and the Feudal Lord of the Kaga Domain, came here on a tour of inspection. Much later on after the Pacific War the well known poet and artist Komatsu Sakyu visited the area of recite his work. Escorted by poets from Wajima, he was invited to visit Ohzawa, arriving by boat rather than taking the precipitous overland route. It is said, however, that he was taken to the Oketaki Falls. The north-westerly wind which blows over the rough waters of the Japan Sea in winter is said by the locals to be so strong that they cannot open their eyes or mouth. So, in order to afford some protection, it has been the custom for the villagers to cut giant bamboo from the mountains to make and maintain a windbreak. |

|

| Historically, Ohzawa was well-known for the large number of woodcarvers who worked there, roughing out the basic shape of the bowls, which have been a mainstay of the wood-turning and true lacquerware industry in Wajima for many years. The work was anything but easy. Sitting on the floor and clamping a block of wood between their feet, they would skillfully turn the block as they hollowed out the inner form of a bowl using a special adze. These roughed out bowls, which where then ready for turning on a lathe, were put into straw bags and sent by sea up the coast to Wajima. There was no bus route along the coast here until 1961, so people either had to travel to Wajima in a wooden boat, or had to walk along a narrow mountain path to get there. They were forced to cope the best they could with the rigors of nature, living a life which was both modest and reserved. Noto itself has been recognized as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System as certified by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. The landscape and culture of the mountain and coastline of Ohzawa and Kami-Ohzawa are now the object of a survey by the Agency for Cultural Affairs in Japan as a culturally rich landscape and environment worth of conservation and something worth preserving for the future. Long may it remain. Shinji Takagi---Architect Born in Wajima in 1942. Worked on many projects using local materials and true lacquer for shops, houses and a variety of interior design schemes. Principal work includes Yuyado Sakamoto in Suzu: the repair and renovation of the true lacquer craftsman’s house, Nurishi no Ie in Wajima: Meiso no Yakata in Toga, Toyama prefecture: the store Kombuya Shirai in Nanao and Kanazawa: a store selling Japanese candles, Takazawa Shoten in Nanao. Member on the Wajima City Council for the Protection of Cultural Properties Committee. Director of the NPO, Ishikawa Reed Thatch Culture Study Group. Bill Tingey---Translator Chief Designer to David Hicks in London before moving to Japan in 1976 and gaining a Masters Degree in History of Architecture. Worked in Japan as a photographer, designer, writer and translator. Returned to UK to continue work in 2000. |

| (2014/7 yuko yokoyama) |

|

(C)Copyright 2004 Jomon-sha Inc, All rights reserved. |